If new features are progress, why do mature systems so often feel slower, harder to change, and more fragile every year?

Quick summary (for busy readers)

- New features create long-term architectural drag, not just short-term cost

- Stakeholder pressure can be reframed using maintenance vs. innovation budgets

- Common enterprise failures are mundane, not dramatic

- Telemetry beats assumptions when deciding whether to build

- Features should have a sunset plan the moment they ship

Why “adding a feature” is deceptively attractive

Features are easy to justify:

- They’re visible progress

- They map cleanly to roadmaps

- Stakeholders can point to them in demos

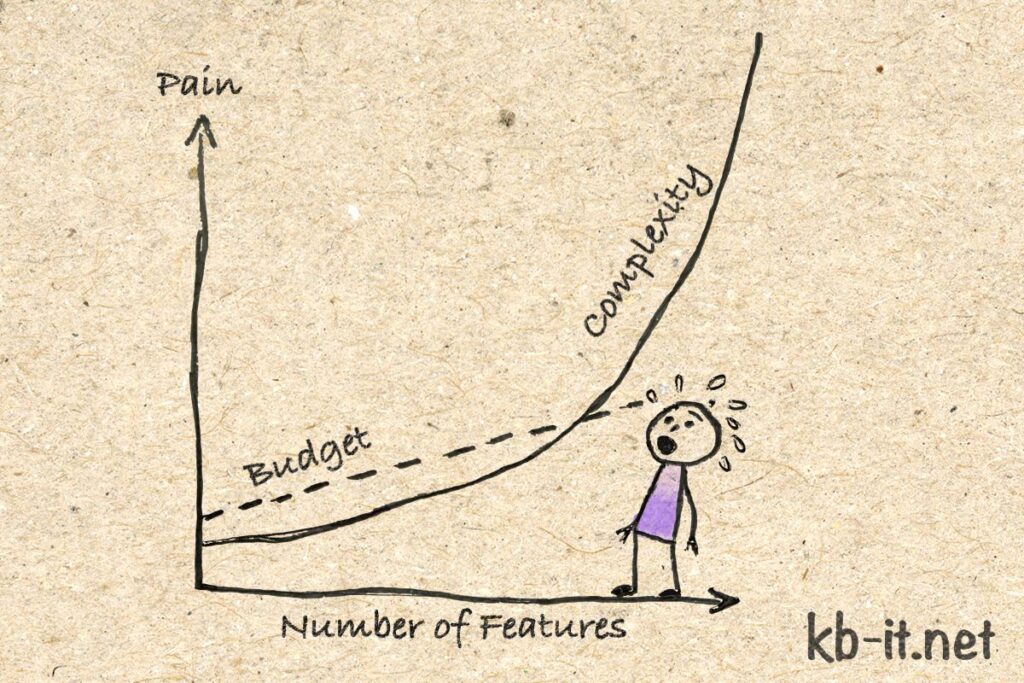

What’s harder to see is the compounding cost curve:

- More code paths to reason about

- More states to test

- More operational surface to secure and monitor

- More cognitive load for users and on-call engineers

A feature is rarely “just a feature.” It’s a permanent expansion of the system’s problem space.

Stakeholder conflict:

How to reframe the conversation

When architects push back on features, the conversation often stalls at “engineering is blocking progress.” Saying “no” rarely works.

A more effective tactic is to reframe the discussion in budget terms.

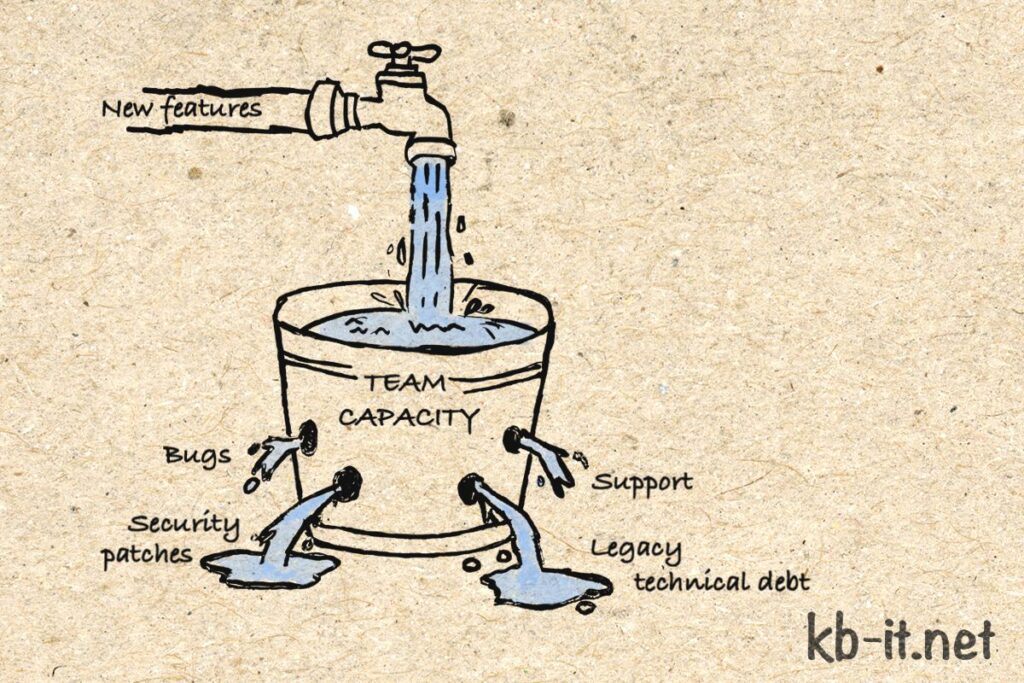

The Maintenance vs. Innovation Budget

Every system has two invisible budgets:

- Innovation Budget – capacity for new capabilities

- Maintenance Budget – effort spent keeping existing behavior stable

New features withdraw from both:

- Immediately from innovation (build cost)

- Continuously from maintenance (bugs, upgrades, support)

Practical tip:

Instead of rejecting a feature, show stakeholders:

- How much of the next 12 months’ capacity will be consumed maintaining it

- What other initiatives that maintenance load will crowd out

You can make this concrete by tagging Jira tickets as “Feature” vs. “Maintenance / Tech Debt” and showing the trend line over four quarters. Once stakeholders see maintenance steadily eating into delivery capacity, the trade-off becomes visible – and the conversation changes.

A more relatable failure:

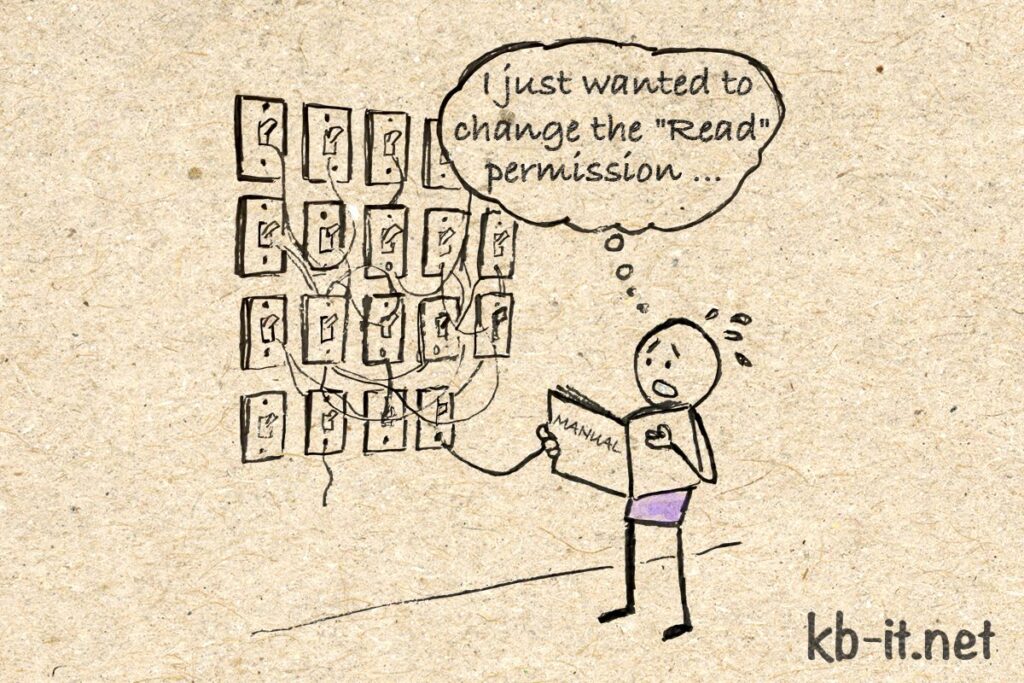

The permissions matrix nobody needed

Not all failures are dramatic. Most are painfully ordinary.

The scenario

A mid-sized B2B platform started with:

- Two roles: Admin and User

- Clear ownership boundaries

- Simple authorization checks

- “Read-only admin”

- “Billing admin”

- “Support user”

- “Temporary access”

- “Regional admin”

The outcome

- A permissions matrix with dozens of combinations

- Authorization checks on nearly every API call

- Slower response times and harder caching

- Engineers afraid to touch auth logic

- Customers confused about what roles actually meant

In hindsight, 90% of use cases could have been solved with:

- Admin vs. User

- One or two scoped toggles (e.g., billing access)

This is how systems rot – not from ambition, but from unquestioned accumulation.

A mental model you can show on one slide

Use this simple comparison when discussing scope:

| Aspect | Feature Cost | System Complexity | Stakeholder View |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth pattern | Linear | Exponential | “Steady progress” |

| Visibility | High | Low | “Looks cheap” |

| Reversibility | Medium | Hard | “We can undo it later” |

| Long-term impact | Predictable | Emergent | “Invisible cost” |

Key insight:

You pay for features once. You pay for complexity forever.

This table also explains why feature debates are so difficult: architects experience the exponential curve directly, while stakeholders mostly see what ships.

Deepened practical example:

Killing a feature before it existed

Sometimes small work can bring big value.

The scenario

A team proposed building a Custom Report Builder:

- Drag-and-drop fields

- Filters, joins, export formats

- Significant backend and UI work

- Number of exports per user

- Columns included

- Filters applied

- Time-to-first-export

What the data showed

- 90% of users exported CSVs with the same 3 columns

- Fewer than 5% applied any filters

- Most exports were immediately opened in Excel and modified manually

The outcome

Instead of a report builder:

- The team added saved CSV presets

- Improved default column ordering

- Added one additional filter

Result:

User satisfaction increased, delivery took days instead of months, and the system avoided a major new UI and data-processing surface.

Telemetry turned a speculative feature into a non-event.

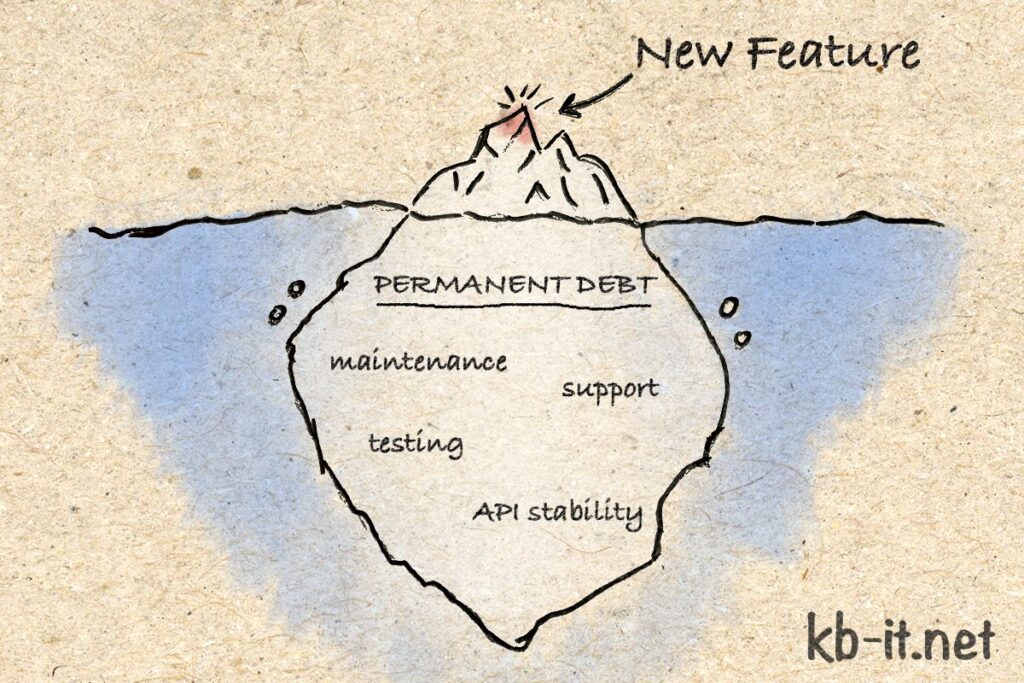

Feature = permanently deployed debt

Think of every feature as:

- A library you must support forever

- A behavior users will depend on

- A contract that constrains future design

- You understand the interest rate

- You have a plan to pay it down

Tactical addition:

The sunsetting protocol

If features are debt, retirement must be intentional.

A simple sunsetting protocol

Add this to your architecture or product governance process:

- Usage threshold – Define “healthy usage” (e.g., % of active users, frequency)

- Owner assignment – Every feature has a named owner responsible for its health

- Deprecation signal – Log usage, warn internally when it drops below threshold

- Soft removal:

- Hide from UI, keep API compatibility

- Add observability hooks (e.g., `feature_used` logs or kill switches)

- If the usage signal stays at zero for 30 days, the risk of hard removal is statistically negligible – even for that “one critical customer workflow”

- Hard removal – Delete code paths, schemas, tests.

Critical warning:

If you don’t practice removal, your system will only ever grow – until change becomes impossible.

Common mistakes (and how to avoid them)

-

Mistake: Treating edge cases as feature justification

Fix: Solve edge cases with configuration first -

Mistake: Building before measuring

Fix: Add telemetry as a prerequisite -

Mistake: No exit strategy

Fix: Require a sunset plan in the design doc

Final takeaways

- Feature growth is the fastest way to lose architectural leverage

- Stakeholder alignment improves when cost is framed over time

- Most value comes from refining what already exists

- If features can’t die, systems eventually will

If you remember one thing:

The best systems aren’t defined by what they can do – but by what they deliberately choose not to.